With The Artist: Why Anju Dodiya Believes Art Is More Than the Hunt For Meaning

Known for contemplative female figures and ukiyo-e-inspired imagery, Anju Dodiya’s symbolic practice spans global biennales and museums, cementing her as a leading voice in contemporary Indian art.

- 10 Dec '25

- 10:05 am by Manisha AR

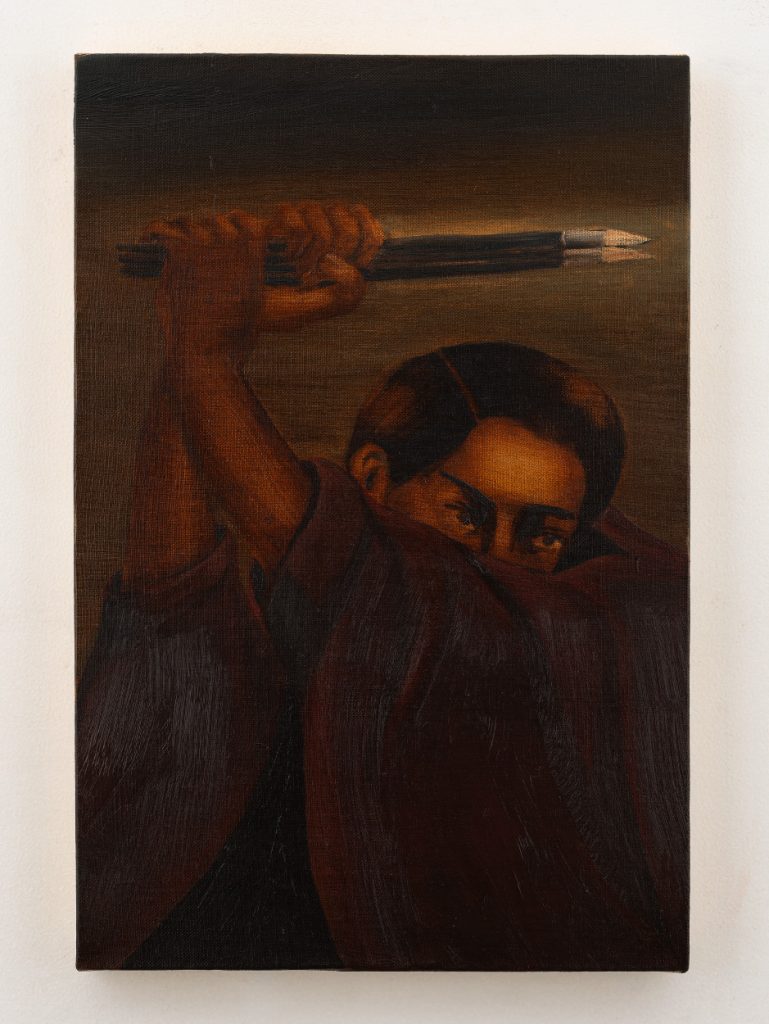

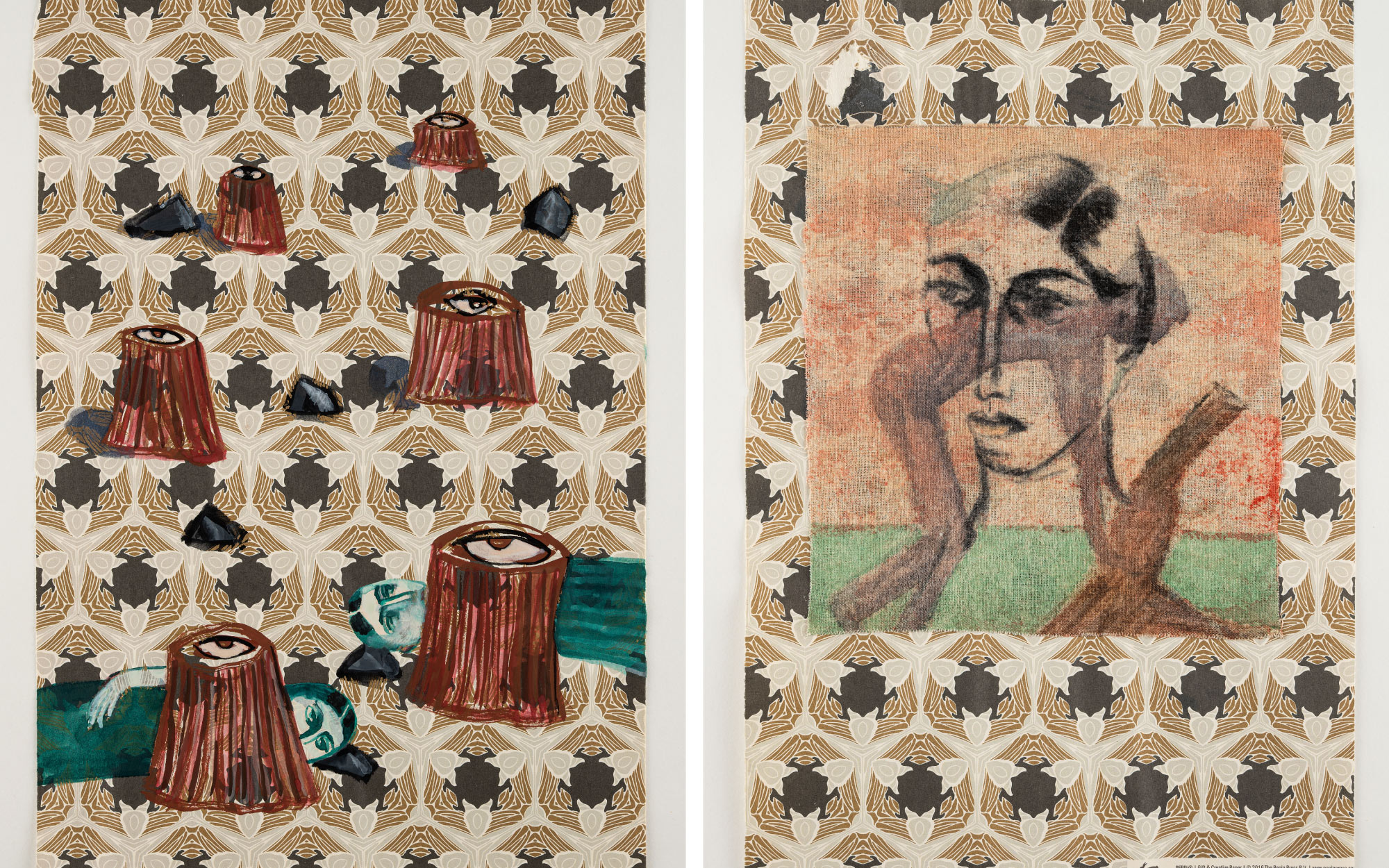

Anju Dodiya is best known for her watercolour-and-charcoal portrayals of pensive female figures. At one point, she also became known for incorporating mattress patterns into her work, and more recently, at Frieze Masters, she presented pieces inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e prints. The most iconic example of this tradition is Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa,’ a woodblock print from the 1600s that recently set a record at US $2.8 million. Drawing on this legacy, Dodiya created ‘The Wave (2014)’, echoing Hokusai’s composition but replacing the central figure with her signature woman pushing a paintbrush forward. A surge of trees—another recurring motif in her practice—rises behind her. The work now belongs to the Burger Collection, Hong Kong.

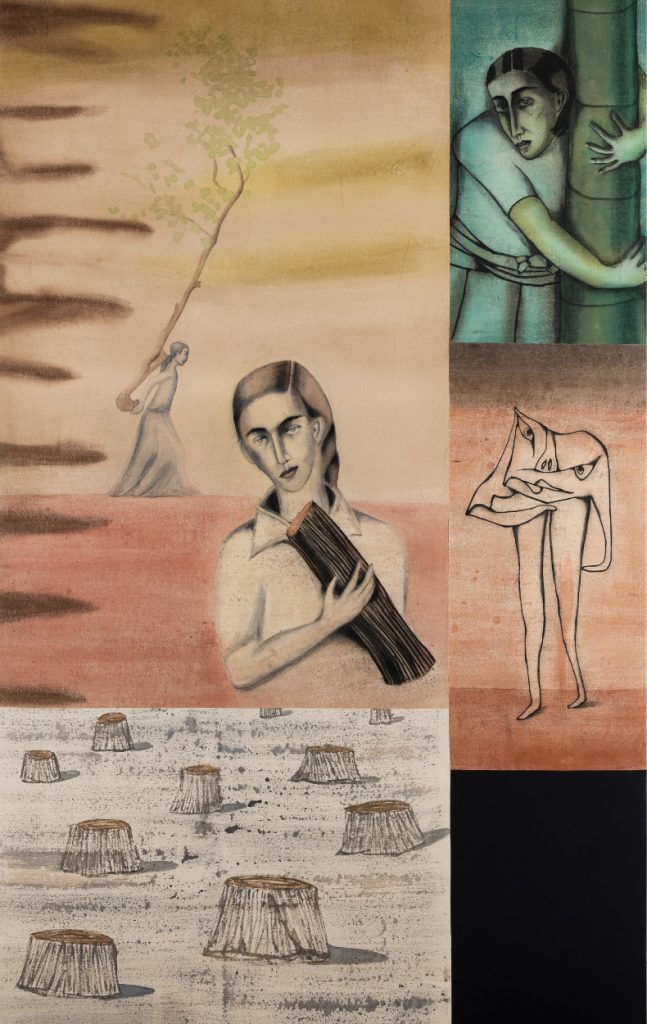

A graduate of Sir JJ School of Art, Dodiya made her Frieze London debut this year, where Vadehra Art Gallery sold three of her works for $50,000 (₹43.86 lakh) each. She described the experience as intimate and engaging, noting conversations with visitors curious about her interest in pre-Renaissance imagery, Catholic saints, and poetry. Her latest solo, ‘Geometry of Ash,’ at Chemould Prescott features her familiar contemplative muses alongside new figures such as the “Log Lady” from Twin Peaks. Dodiya’s trajectory spans the Sharjah Biennale (2023), Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2018), and Venice Biennale (2009), among numerous global exhibitions. Her works are held in major public and private collections, including the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and Tate Modern.

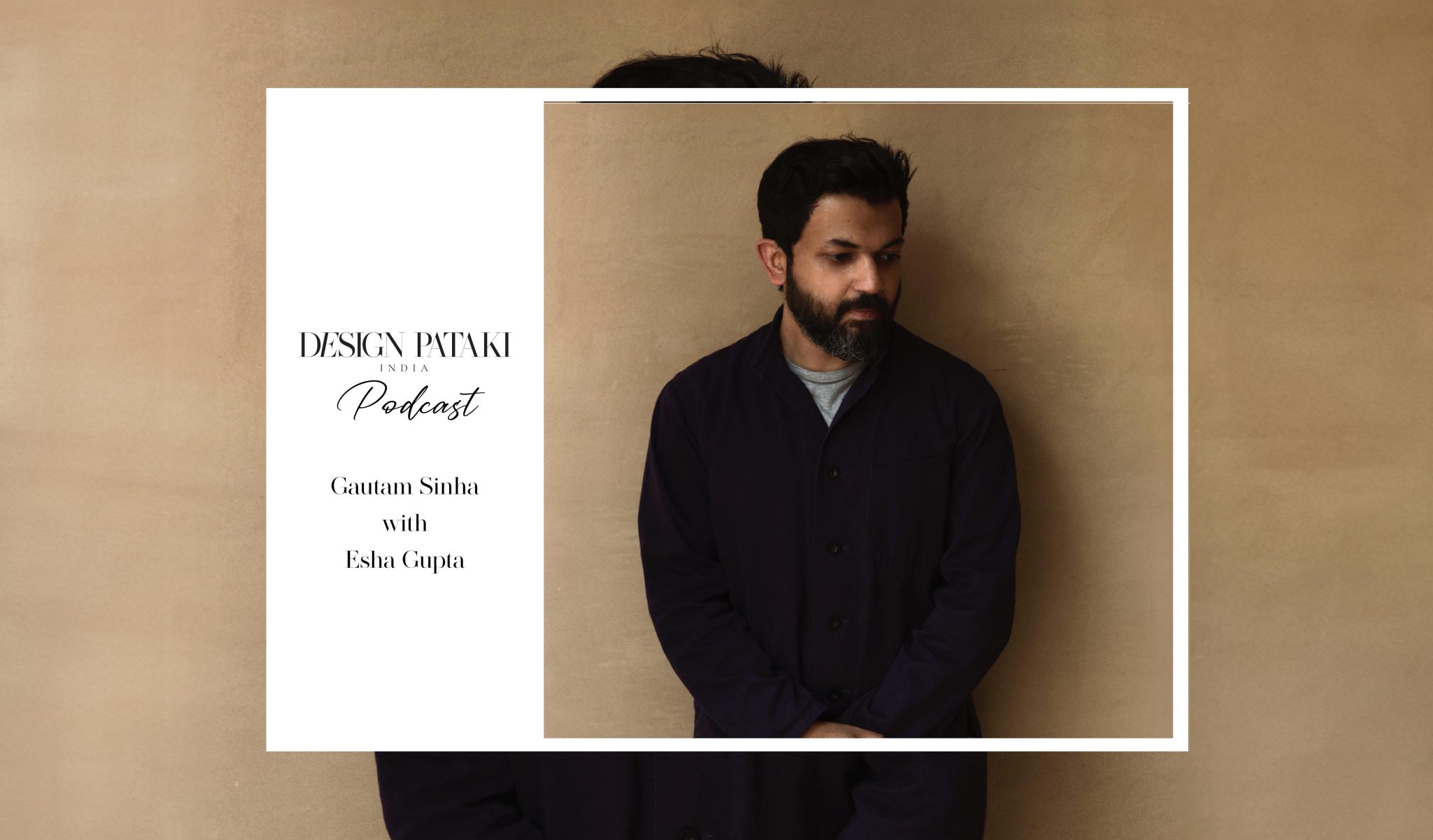

In this conversation with Design Pataki, we trace the evolution of Dodiya’s artistic language—from her psychological interiors and symbolic visual vocabulary to her expanding international presence and the influence she holds over a new generation of contemporary painters.

Also read: Marking Her Debut At Frieze 2025, Anju Dodiya’s Paintings Fetch $50,000 Each

What’s one thing people might be surprised to learn about your creative process?

Like hibernating animals, I have slow months in the studio when nothing ‘major’ seems to happen. After that, a rapid ‘summer’ brings a fast, full harvest of work. This has been an ongoing cycle for the past few decades. Earlier, this would scare me, but now I accept it as an inevitable process.

What role does discipline or ritual play in your studio practice today? Are there rituals that help you step into the psychological space your work demands?

I am disciplined, in a chaotic fashion. I try to work every day, but the major chunk may happen in the evenings between five and eight or sometimes, after dinner. I might listen to one singer while making an entire body of work. Just on repeat. And I always find time for watching movies, even while chasing deadlines.

“Cinema nourishes me and helps me forget myself, and paradoxically, returns me to myself, in new imagined states.”

Many of your works often hover between autobiography and theatre. Where does this new exhibition sit on that spectrum? Do you sense a shift toward abstraction, restraint, introspection or something new altogether?

The autobiographical element has always been fictional! So the many personas may resemble me, but enter new roles and possibilities. In this exhibition, ‘The Geometry of Ash’, the scale allowed for diverse scenes to play out in one larger space. It suggests narratives, but allows the viewer to slip into quiet spaces. I think there is less drama and more subtle emotions are at play.

Also read: 5 Indian Artists At The Berlin Biennale 2025 Who Are Redefining Contemporary Art

A material you can’t live without in the studio.

I better say my Staedtler pencil. Some stock of charcoal.

Drawing or painting — which feels more like home?

Drawing defines. Painting gives it air and weight.

Who is an artist you’d love to have a conversation with?

Fra Angelico. About his life while painting in the monastery in Florence.

In ‘Geometry of Ash,’ what does the notion of ‘ash’—literal or symbolic—represent for you, and in what ways does geometry serve as a structure for engaging with that idea?

The absurdity of geometry and it’s perfect aspirations against the horrific reality of our times is what I was thinking about. As an artist, one obsesses over formal structuring and order, all the time. The overnight defacement of cities and the destruction of an entire civilisation in this context, reminds you of the turbulence we live with. There is no mystery about an apocalypse. It is only about ash and endings.

‘Log Women’ evokes Twin Peaks’ Log Lady even as it shows a woman cradling a tree. Is the wood a symbolic anchor in this work—something the figure, or we as viewers, are being asked to hold onto?

Yes, the log image anchors most of the paintings. The beauty of trees and the pain of deforestation is ours to bear. I think that each tree is an ancient ancestor, witness to each act I perform, witness to history. Visuals of the Chipko revolution come to mind, of women hugging trees. Slender, strong, bent bodies carrying wood, the weight of centuries, walk the hills. Watching David Lynch’s log lady in ‘Twin Peaks’ moved me. This woman omnipresent, carrying this log! Like a beloved child or a precious bag of jewels or as labour; or a logbook of the days and nights she has lived.

Across your long career, are there specific moments like shows, bodies of work, or even single paintings, that you feel redirected or transformed your practice?

I continue to feel that ‘Throne of Frost,’ a site-specific installation at the Baroda Palace in 2007 was a landmark work for me. I stepped out of intimate zones into a very special, glittering, emotive space. There was drama and the viewer became a performative, engaged element.

Also read: Art Confidential: Abhinit Khanna On Playing The Long Game When Collecting

My love for the Japanese Ukiyo-e prints often throws me into dreaming about making many long screens. Many. Dividing a room. Transparent, opaque, erotic, geometric.

A recurring symbol in your work that still reveals new things to you.

Not symbol. But the Japanese Ukiyo-e prints still feed my art. The linear gestures, the grace. For the last 30 years.

Global art fair or intimate gallery show — what brings you more joy?

Gallery show. Controlled space. The people around you.

Also read: M.F. Husain Museum Is Set To Open In Qatar This November

Your Frieze London debut received strong attention. For an artist deeply rooted in the interiority of the self, does global visibility influence or complicate your relationship with audiences?

I showed at Frieze Masters, London, in a section called ‘Studio’. This was curated by Sheena Wagstaff, a sensitive senior curator. This showing had some new works, older works, and a small vitrine with studio paraphernalia like postcards, reference images and a small sculpture from my desk, etc. Overall, it felt like a special small exhibition, and it wasn’t like an art fair outing, at all. In fact, I had many interesting conversations with viewers and artists taking pictures, asking questions about my interest in pre-Renaissance paintings, catholic saints and poetry.

Emerging artists often cite you as a major influence. How do you feel about your role in shaping a generation’s approach to vulnerability, self-portraiture, and psychological intensity?

That’s humbling to hear because I struggle every day with my own creative problems. One hovers between truthful vulnerability and heroic aspirations in the studio. I think I have made THAT the subject of my art often, and that pulls the rug from under the romantic idea of the maestro artist who understands and performs. Perhaps, I allow myself and others to hesitate. To flounder. And that allows for a slowly evolving freedom.

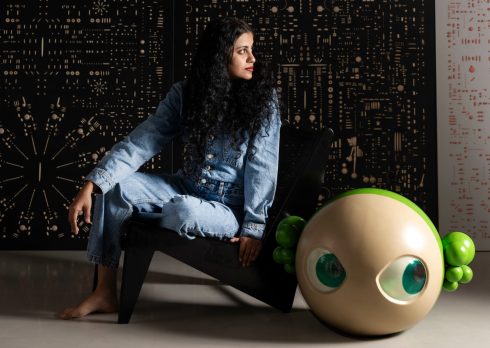

India’s cultural landscape is shifting rapidly. How do you think contemporary Indian art is responding to the pressures of politics, technology, and global visibility? Does any of this seep into your own concerns?

Young Indian artists are doing diverse, dynamic art. I often find it inspiring – the range of materials explored, the courage of a very alert political awareness; at the same time, the young viewership expands. However, I often worry about one thing – that the Indian art scene is fixated on meaning! The subject explained is not the art. The note alongside the work is not the work. Materiality in art, the stain, the mark, the hard, the soft that construct, gives it meaning. Otherwise, we will just illustrate ideas. Doris Lessing has said somewhere in ‘The Golden Notebook,’ that to have a politically/morally important subject does not ensure great art. Craft and form elevate the subject and take it elsewhere, to become art.

Her latest solo, ‘Geometry of Ash,’ is on view at Chemould Prescott Road until 24 December 2025.