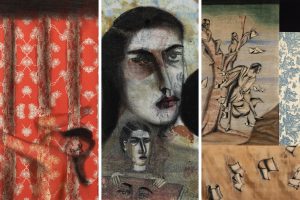

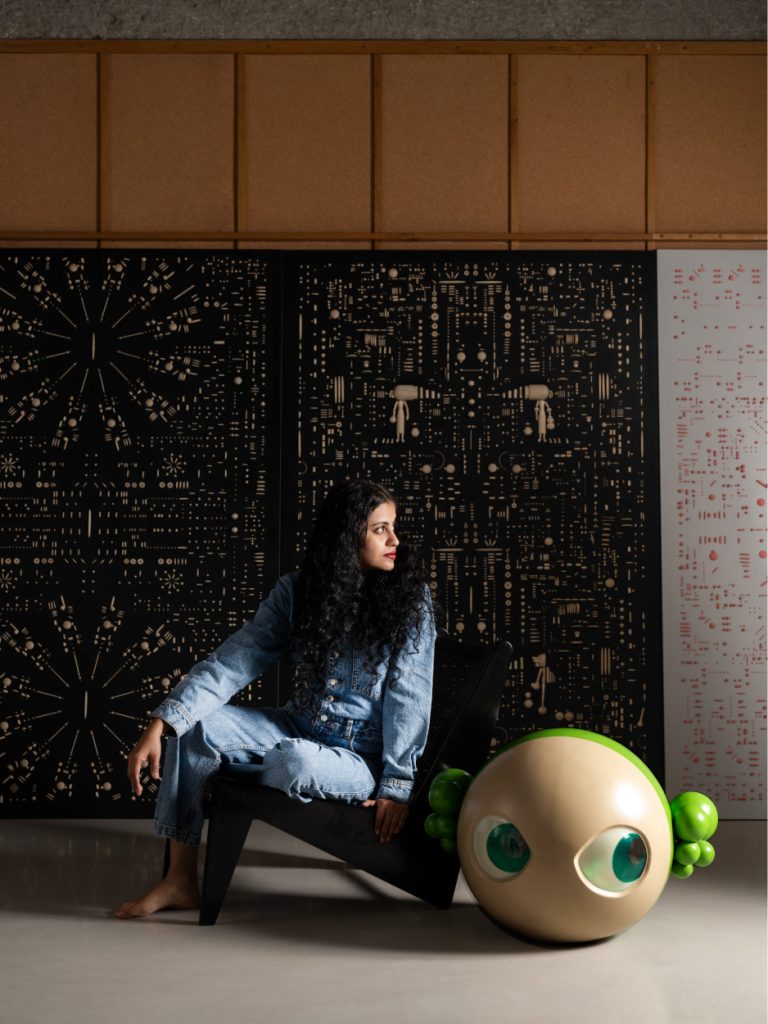

With The Artist: After 16 Years, Princess Pea Finally Reveals The Face Behind The Peahead

In conversation with Indian artist Natasha Preenja, we unravel the persona behind the famed ‘Princess Pea’. After 16 years, she finally takes off her oversized pea-shaped headgear while presenting her latest solo at TARQ.

- 16 Dec '25

- 11:04 am by Urvi Kothari

Anonymity was the force of curiosity around this Indian artist who identified herself with an oversized pea headgear anime for 16 years. The character’s presence became a conversation starter at its debut appearance in 2009, when India Art Fair known as India Art Summit, was held at the iconic Pragati Maidan. This exaggerated headgear with doe eyes and green bunned hair personified Natasha Preenja’s alter ego, Princess Pea. By concealing her identity, her persona challenged patriarchal norms and preserved intergenerational wisdom in a way that no single person is able to. Her practice includes collaborative, time-based, and intervention-led work, fostering a growing community of camaraderie among diverse women. In 2008, Preenja founded THE PEA FAMILY Studio, which has a decade-long collaboration with traditional toy artisans from Etikopakka, a coastal village in Andhra Pradesh. Her noteworthy projects include Proxies presented at India Art Fair 2019 that blurs the idea of self while questioning notions of identity, absence and presence. Her works are part of notable collections such as the Mead Art Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts, and The Museum of Living History by Mahindra, Mumbai. She is also the recipient of the inaugural Swali Crafts Prize 2025.

Despite the acclamation, for 16 years, connoisseurs continued to ask – Who is Princess Pea?

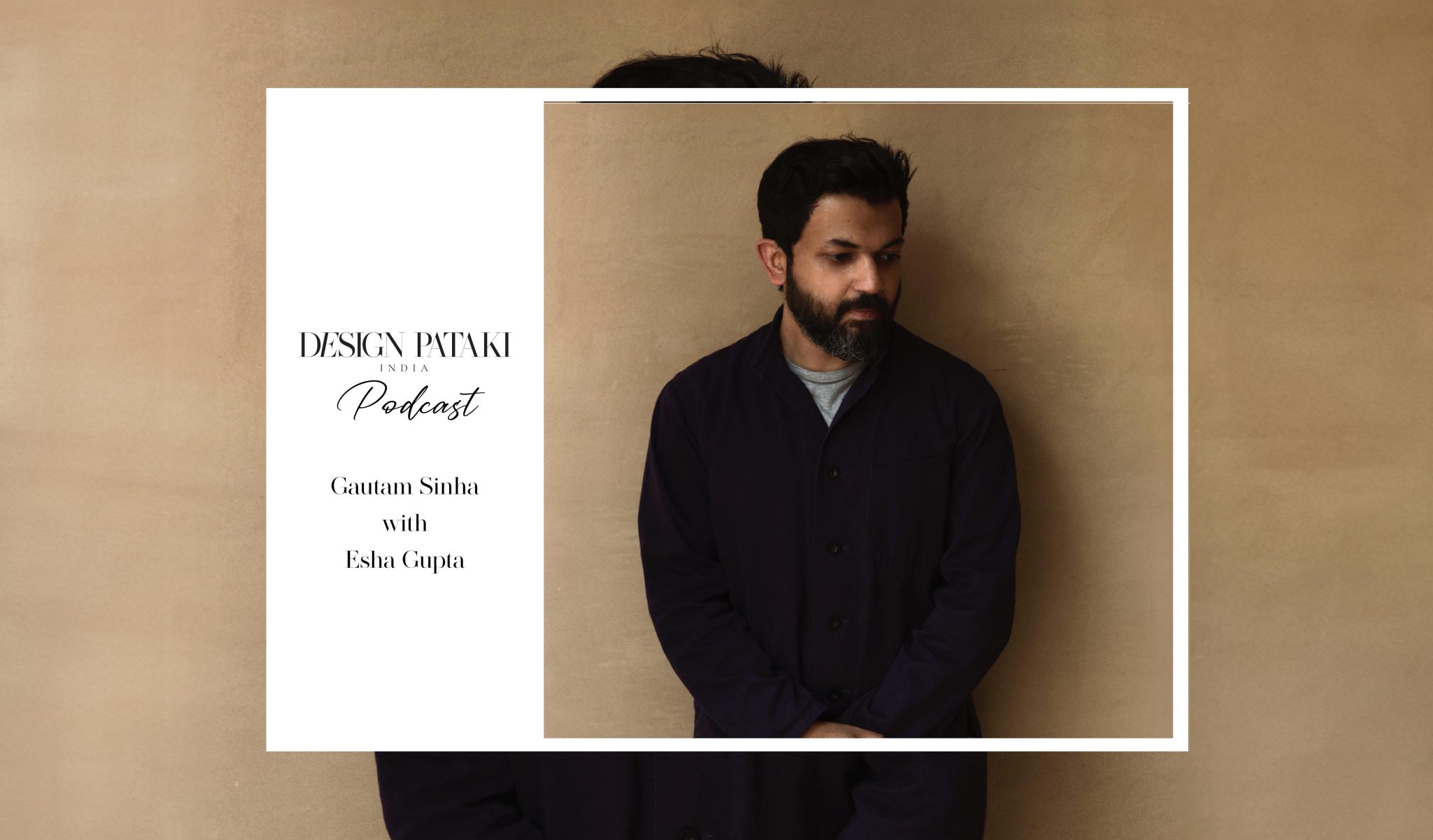

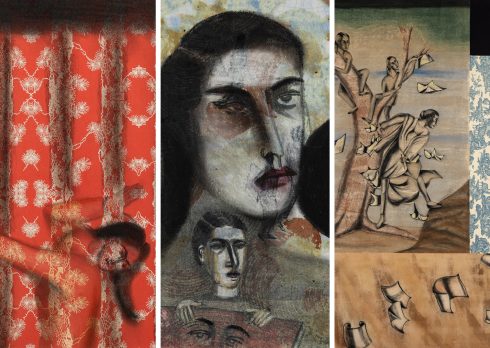

All one knew was that she was born in Ferozepur, studied in Delhi College of Art, and currently lives in Gurugram. The name and face behind the huge clay head continued to be a mystery for the world. Until recently, on November 6, when she decided to let go of her mask and unveil her identity with the opening of her latest solo exhibition titled ‘वज़न’ at Mumbai-based TARQ. The exhibition invites viewers to reflect on identity, society, and tradition, while forging a community to sustain intergenerational knowledge of traditional crafts. Spanning across diverse mediums and reflecting on years of exploration, Preenja reframes the female subject not as muse or passive form, but as a site of endurance, resilience, and quiet strength. In conversation with Natasha Preenja, Design Pataki dives deep into her artistic practice, inspiration, ongoing projects and much more.

Design Pataki: What’s your perception of the term ‘वज़न/ Wazan’?

Natasha Preenja: Throughout my life, this word has continued to evolve and change. For as long as I can remember, I have grown up trying to understand the meaning it carries in a woman’s life.

It’s about the heft of the body, as material, as status; it holds different values at different times.

It can be the time I spent inside my mother’s womb, or now, as I carry my own child, the weight we have taken across generations.

This exhibition becomes a way to measure that invisible weight, one that women have borne quietly throughout history.

DP: After 16 years, you’ve stepped out from behind your iconic headgear. How has that felt, personally and artistically?

NP: Over the years, I’ve felt these gestures overlap; the self and its reflection trade places, share roles, quietly lending themselves to one another. We forget this daily performance, this silent choreography of pleasing and proving, as we seek small approvals in every breath we take.

As my practice evolved from the ‘self to others’, I began to sense the shift within me.

From a girl to a woman, and now a mother. We play roles, we change, we age, and expand our own selves into more – more care, more resilience and more ways of being.

With my growing inclination toward community practice, I feel that ‘Princess Pea’ has also expanded, no longer a single self, but an infinite woman.

DP: How do you view the relationship between Natasha Preenja and your alter ego Princess Pea, now? Are they separate, overlapping, or something else?

NP: I want you to think of this – standing before the mirror, every morning, every day, you lift the brush, smooth your hair, and trace a line of colour across your face.

In these quiet moments, as you apply makeup and comb your anxieties away, a familiar rhythm emerges, and gestures repeat themselves, beginning to blur.

DP: In the exhibition description, there’s an emphasis on ‘intergenerational knowledge’

and ‘domestic economies’. How do you see your work engaging with these ideas?

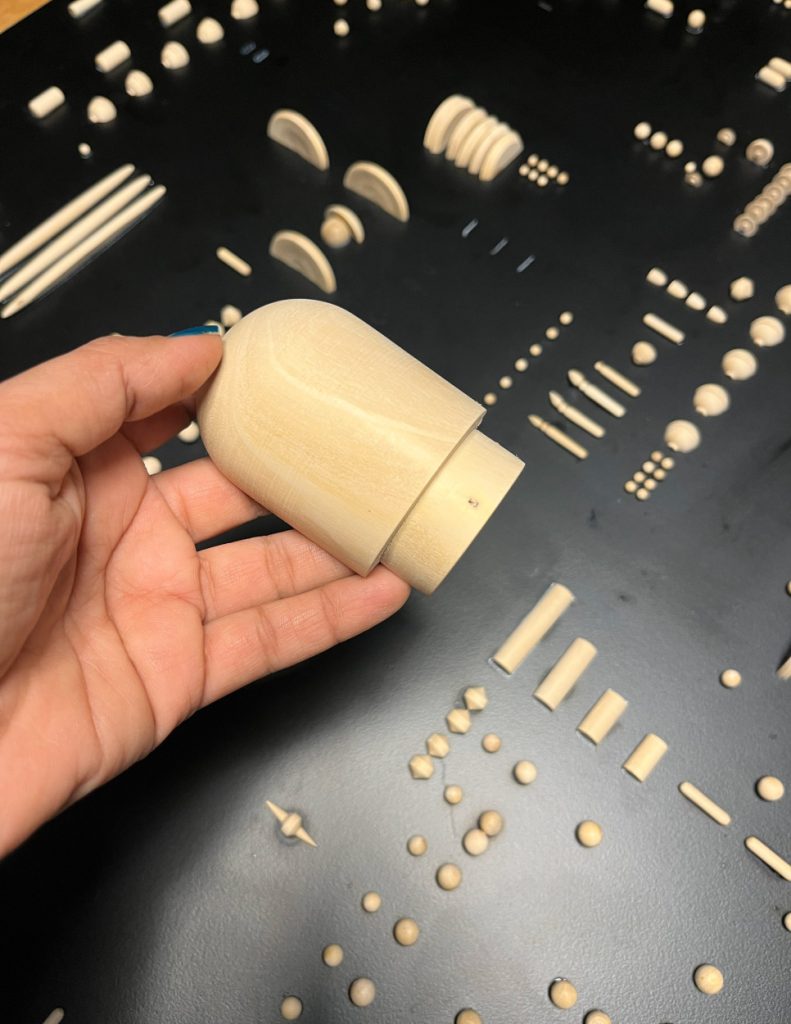

NP: I am interested in the kinds of knowledge that are passed down across generations, whether it is the craft practices in toy-makers’ villages, where artisans have been turning this homegrown wood for decades, with entire families sustaining themselves through it, or the domestic wisdom held by my mother, grandmother, and the women before them. This knowledge is carried closely, almost protectively, and shared with the next generation through everyday gestures.

It is a warm, resilient energy that holds families and, in many ways, society together. Craft, after all, has always been a domestic affair. Women in the home have long been integral to making, preserving, and keeping these traditions alive.

DP: Listening is often described as an ‘ethical framework’ in your practice. Can you talk about how listening shaped the works on display?

NP: My ethical framework is grounded in ethical listening. For me, listening is not passive; it is an act of respect and responsibility. It means being attentive to the rhythms, boundaries, and silences of the communities I work with, and ensuring that their knowledge is neither taken for granted nor instrumentalised.

Equally important is the commitment to maintaining relationships. My work does not end with the completion of an artwork. I continue to learn from the women and families who open their homes and histories to me. This ongoing relationship-building ensures that the practice remains reciprocal, accountable, and rooted in trust.

DP: The show seems to create a ‘collective consciousness’ through your interactions with women of different ages and backgrounds. How important is collaboration and shared labour in your creative process?

NP: These pieces are not created within a single period or only for one exhibition. They emerge from a long practice shaped by different craft traditions and deeply influenced by texts, conversations, and lived experiences. My approach has always been simple: to stay close to what feels real, to allow time to guide the process, and to resist shortcuts. I think of it almost as mothering the work, bit by bit, step by step, with patience and care.

DP: How has your interaction been with women artisans from Etikoppaka, a coastal

village in Andhra Pradesh? Any anecdotal recollection while collaborating with these

artisans for this series?

NP: When I was standing in the turn-wood workshop, I could see that every lathe [machine for shaping wood] had its own rhythm, its own quiet personality. The way their [women artisan] body leaned into the tool, the way her weight balanced against the turning wood, how her breath synced with the rotation, it all felt like a choreography of precision and intuition. Their hands spoke through the tool, transferring thought into touch, as if cognition itself is being shaped into form. These constant shifts of energy, attention, and control feel deeply poetic.

Now imagine this unfolding not for a few moments, but across days, months, and years. Each turn, each repetition becomes a daily ritual, shaping not just the material but the maker herself, where labor transforms into rhythm, and rhythm into memory.

DP: Your marble sculptures ‘Mothers, Bodies of Stone’ are very striking. What does using marble signify in this context, especially given its historical associations?

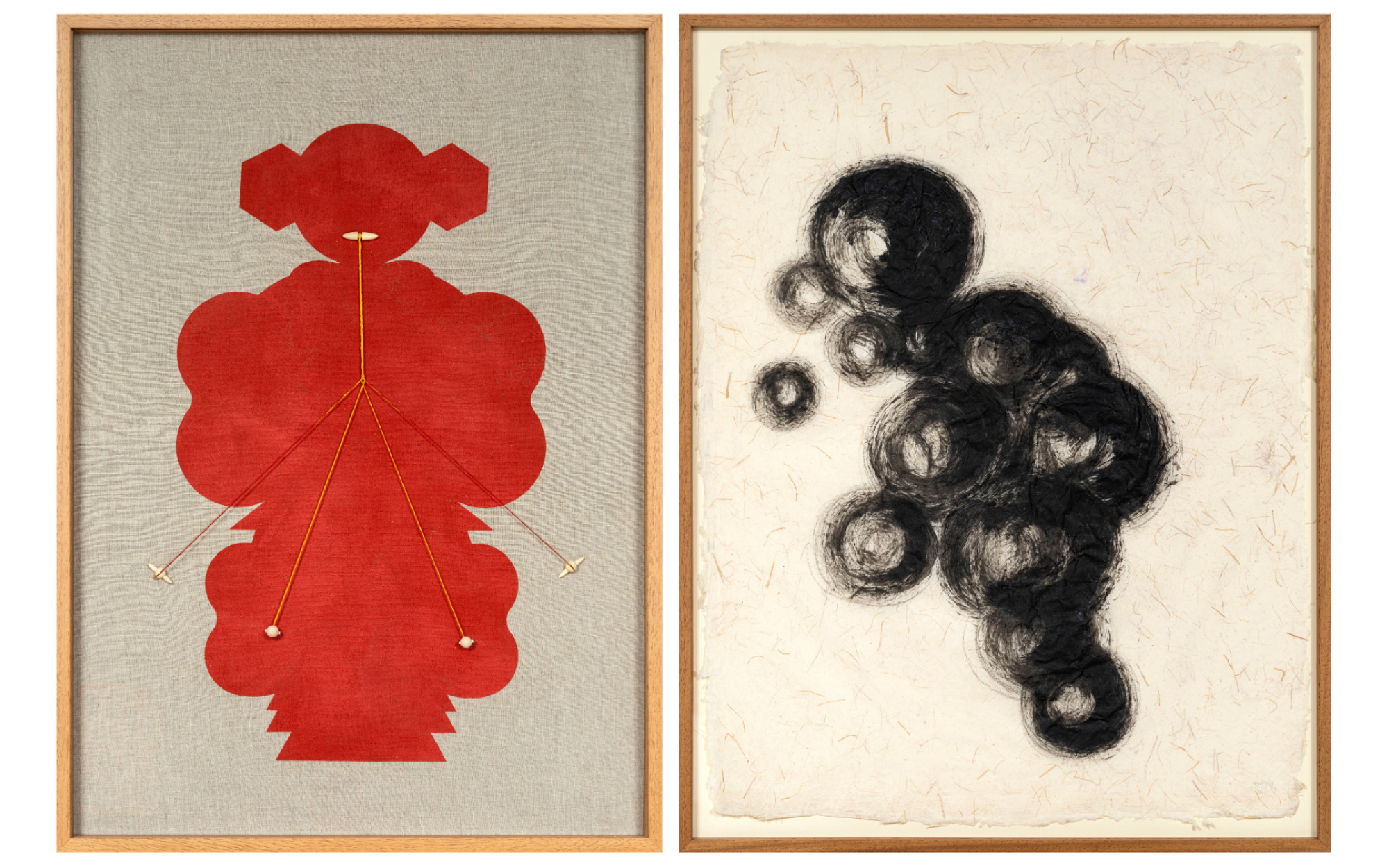

NP: After years of working with wood, I felt limited by my earlier forms and proportions. This led me to marble, a material that teaches its own discipline and reshapes the way one approaches form. I drew from the thousands of sketches I have made over the years, enlarging selected drawings and translating them into Indian marble, allowing them to gain a new scale, weight, and presence within my evolving practice.

The marble, indeed, has its own notes to make, its own pace, resistance, and quiet instruction. By carving in marble historically associated with permanence, monumentality, and a masculine lineage of sculptural tradition, I attempt to reclaim the material through a feminine gaze. The female body, often cast as muse or passive form, becomes instead a site of endurance, labour, and quiet strength. The work strives to shift marble’s legacy toward one of care, resilience, and the everyday heroism carried by women, grounding monumentality not in dominance but in tenderness and survival.

DP: Your drawings use kajal made in your kitchen, combined with kumkum, thread, and traditional pigments. How do you see domestic rituals influencing the physical process of making your art?

NP: The kitchen is my laboratory, a place of constant experimentation in mixing, layering, and applying materials. My ongoing experimentation opens up hidden meanings about what it is to be a woman living in a home, making a home, and simultaneously nurturing an artistic practice. It is in these everyday gestures, stirring, grinding, blending, that domestic labour and creative inquiry quietly converge.

DP: What is your starting point: form, material, story, or emotion?

NP: Story and emotions are predominant; these narratives then derive material and form.

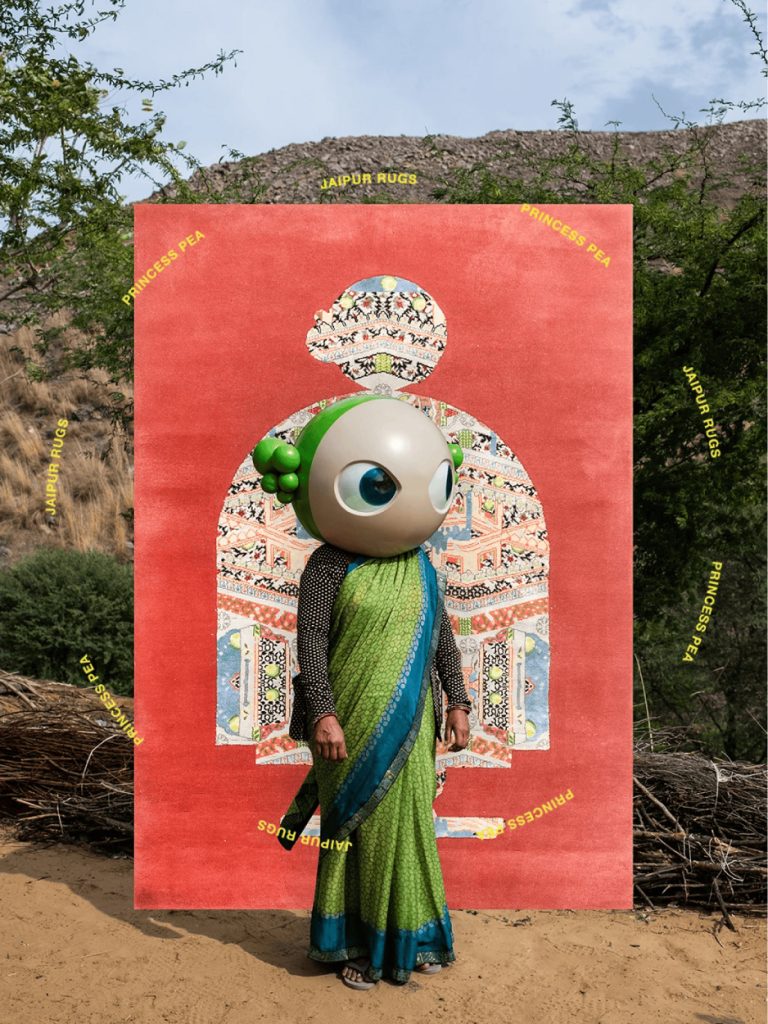

DP: The carpet collection in collaboration with Jaipur Rugs is titled DAYS, and it’s inspired by the menstrual cycle. What made you choose menstruation as the conceptual foundation?

NP: The Jaipur Rugs Foundation with its vast archive and living ecosystem of craft, offered a rich ground to engage with. It was a dream to work closely with the weaving clusters and to understand how the act of carpet-making becomes a safe space for women, allowing them to weave their thoughts, emotions, and everyday realities into tangible form.

As I have been exploring themes of reproductive health and mental well-being, I felt there needed to be a way to speak about these intimate and often silenced subjects within a patriarchal society. The first collection of four carpets, titled DAYS (“Un Dino” – “Those Days”), reflects on the days of menstruation, a time when women are often excluded from rituals and deemed impure. Through this series, I wanted to reframe that narrative, transforming these days of isolation into moments of reflection, strength, and collective care.

DP: Do you see this collaboration with Jaipur Rugs as part of a larger mission – to bring more ‘invisible labour’ into the conversation through art?

NP: There are thousands of women working within domestic spaces, weaving for months while caring for their children, often to the point of forgetting themselves. This invisible labour is what I want to bring into focus, to make visible the care, exhaustion, and strength that remain unseen. Through the work, I hope to create space to think seriously about attention to women’s reproductive health and the conditions under which this labour is carried out.

DP: What does the next chapter of Princess Pea or Natasha Preenja look like for you?

NP: Princess Pea continues to create compelling work that represents women and their invisible labour, honouring them in the belief that the intergenerational knowledge carried and passed down through women forms the backbone of collective memory and survival.

The persona behind Princess Pea isn’t disappearing. She’s just expanding – from one woman to a collective consciousness. वज़न by Natasha Preenja will be on display at Mumbai-based TARQ until December 24, 2025.