From Kanye West to Virgil Abloh, meet an architect at the intersection of Pop Culture and Design

“People tend to laugh out loud when I say that Carter III was an integral part of my thesis project. Not sure why, I don’t think it is funny and I definitely do feel architecture could use a little more of Lil Wayne’s spirit. And then you do realize, as if you could ever forget, that the field is largely represented by a different generation, which you have next to nothing in common with. By and large architecture is in a rut and a rather dull moment. There is very little that blows your mind and I desperately want my mind to be blown.”

It is hard to put a label on Oana Stanescu. She may be an architect in the conventional sense, but through her remarkably heterogeneous body of work, constantly redefines the meaning of the term. Stanescu grew up in Resita, a small town in Romania that was in the violent throes of a revolution at the time. Persevering through her circumstances, she studied architecture and went on to land an internship the Office of Metropolitan Architecture in New York. Following that, she worked at prominent design firms in Japan and Switzerland, volunteered with Architecture for Humanity in South Africa, and founded two architecture practices in New York – Family with Dong Wing Pong, and a recently established solo venture under her own name.

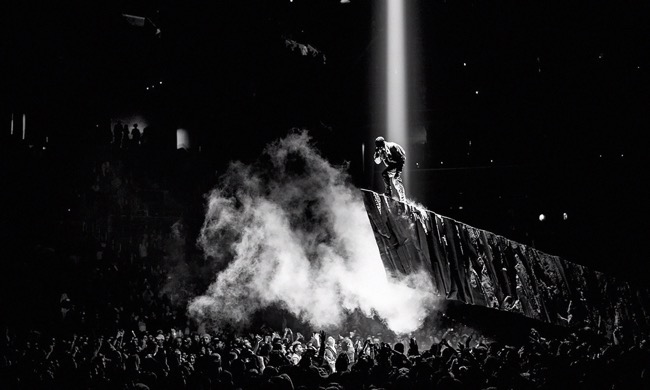

While her design ventures are inarguably varied, Oana Stanescu’s fame stems primarily from her ability to blend popular culture with architecture. Her most notable project is the stage design for Kanye West’s grand Yeezus tour, which featured a 50-foot volcano for him to ascend onstage. She met the rapper during her time at OMA and went on to develop a close working relationship with him – to the point where she was amongst the very few who sat in on the recording of Yeezus, which remains West’s most famous album to date.

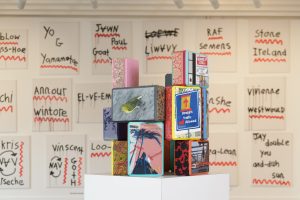

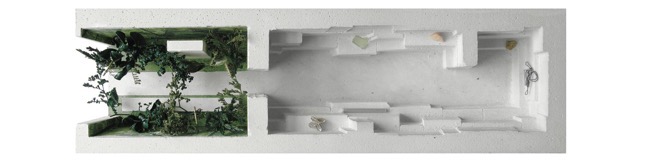

Stanescu also collaborated with Virgil Abloh who recently made history as Louis Vuitton’s first ever African-American creative director. Along with her (then) partner Dong Wing Pong, she designed the Hong Kong flagship store for Abloh’s high-end streetwear brand, Off-White. Their highly innovative vision for the store focused less on traditional merchandising and more on creating a unique customer experience. While neighboring brands sported conventional window displays, Off-White opened with a beautiful interior garden that led one into the store.

Another one of her more inventive undertakings is the +POOL project, which reflects Stanescu’s creative philosophy of putting people and their communities at the forefront of design. The project was conceptualized 8 years ago by her and Dong Wing Pong with friends Archie Lee Coates and Jeffrey Franklin of the office of Playlab, and looks at installing the world’s first water-filtering floating swimming pool in the East River, New York. Eschewing a more conventional developmental model, the duo took to Kickstarter to generate funding.

We asked the architect about her relationship with popular culture, her inspirations and her design journey.

1. How has your love for pop culture and music shaped your design sensibilities?

A lot of it happens in an indirect way, as everything you ingest is affecting your view of the world at a subliminal level. More recently though, in the last few years, the private barriers between different fields have been coming down. Meaning I see the music I listen to, the conversations I am having, the books I am reading, not as separate but directly affecting my work and my every day too. It’s hard to put into words but it comes down to having a specific worldview, values, goals and desires and a big effort goes into making sure the work is reflecting this.

There is nothing that affects us the way music does for example, and I often try to ask myself how can an architectural project bring us closer to that deep, immeasurable dimension, to the unspeakable that is in all of us.

These days I am listening relentlessly to Solange’s new album for example and so I am constantly double checking if I can come closer to being as unapologetic, to dive deep and be as fearless about self-expression, and ultimately, to question but not doubt myself. And this applies to the effect of architecture just as much as it does to the representation and ideation.

People tend to laugh out loud when I say that Carter III was an integral part of my thesis project. Not sure why I don’t think it is funny and I definitely do feel architecture could use a little more of Lil Wayne’s spirit. And then you do realize as if you could ever forget, that the field is largely represented by a different generation, which you have next to nothing in common with. By and large, architecture is in a rut and a rather dull moment. There is very little that blows your mind and I desperately want my mind to be blown.

That’s where popular culture, or music or movies or books come in because they reflect the society’s spirit and temperature in a way that architecture, which needs a lot of time to materialize, just simply cannot. And given that we are in such critical times I do feel that architecture not only needs to play a role in the now but can productively contribute to the conversation. If architects continue to be distracted by nostalgia, if we don’t let go of the notion of what the architect once was, we risk living in a world shaped by everyone but architects.

2. Your diverse body of work ranges from building community centers in South Africa to stage design for Kanye West. What draws you to a particular project?

I am incredibly lucky to have worked over the years on some amazing projects, with some amazing people. Probably one of the most important aspects is learning what or whom to say no to, and that’s not an easy thing to get to. The critical thing is who you get to work for or with. If there isn’t a sense of trust and good communication there, then there’s no point in even trying because it is like a relationship and you depend on one another. Outside of that, I have a vested interest in culture, arts, education and public programs, always looking for a larger scale impact.

Also, all if not most architectural projects are operating within a given set of parameters, somewhere between limitations and opportunities. This unique set of circumstances is what I always find to be the most part of a project, begging the question of how to turn constraints into opportunities. It is never the lack of resources or seeming impossibility of a project that ever makes me say no, nor the size or program or scope, it is really just the overall ambition and implicit goals behind it. If they align with mine, then I’m in.

3. What inspired your design for Virgil Abloh’s Hong Kong store?

Virgil! It was the first space for Off White and we kicked things off by strolling through Chelsea galleries and talking about his ambitions with Off White, with the rest of his work and beyond. I am not sure what we saw but tangentially discussing the art and neighbourhood we were passing through also enabled us to set goals for the project. From there it was all about tossing around ideas. We did want it to stand out on Patterson Street, it had to, given that we were surrounded by all these established brands. But we also wanted it to be generous towards the city and people, inviting and welcoming. I see the point of Off White like that of a pin up (a type of conversation that is at the heart of all architectural education), an excuse for a broader, ever-evolving conversation and the space had to enable that. We also always anchored all Off White spaces into a reaction to local conditions. In the case of Hong Kong, we wanted to bring the natural, the greenery into the concrete city.

4. From a then politically unstable Romania, you’ve established your base in New York and have worked your way across the globe. What have been your most significant learning experiences with reference to culture and design?

The best thing about the learning process is that it is endless, so every time you think you climbed a peak, you start seeing the next one. The probably biggest insight that came from working and living on different continents was understanding how there is not a singular way of inhabiting architecture, just as there is no singular way of creating architecture. The exposure to different ways of life helps you understand yourself a lot better, particularly the parts that are learned and were never questioned, which are deep within all of us. But understanding that those parts too can be changed or chosen, is important. Ultimately I found it to be a very liberating process which incentivizes one to carve their own path, their own way of looking at architecture, their own culture. And my biggest struggle is always with people who believe the opposite, who are so ingrained in their own place that they start believing that it is the only way of thinking of architecture. It might be, but only for them, and if there is no awareness of the multiple ways of being and doing that, then we are robbing ourselves of what the world could be. All of that being said there are also a couple of things that are becoming more and more urgent on my radar, one of them is incentivizing the generation to come. They have will face a world that will be fundamentally different than even what my generation went through, and so I always wonder how we can operate with a foot in the future. Certainly educating in the same way as 50 years ago can’t be the answer, so education is one of the first places that has to leap.

5. Have there been any recent developments on the +POOL project?

Yes! Due to an outpouring of support from vocal community members, the whole CB1 board voted YES last week to incorporating + POOL into the Brooklyn Bridge Esplanade. + POOL is now officially being recommended to the mayor so it’s about to get fun.

This is huge because such a project requires a variety of stakeholders coming together- from the mayor to businesses to the city council and residents— and so community board support is a big part of that process. But outside of that, the biggest challenge with innovation, with doing something that hasn’t been done before is exactly that: there is no predetermined path to follow and so everyone, and I mean everyone, from the city to the different departments to designers and scientists and lawyers and swimmers, everyone has to come together to also invent the right path of implementation and hopefully set a productive precedent for the city. All of this effort is necessary just so we can reclaim the river and swim in the summer. Next interview we can do in the pool!

Photographs Via Family New York