The Complex History Of Chandigarh Chairs

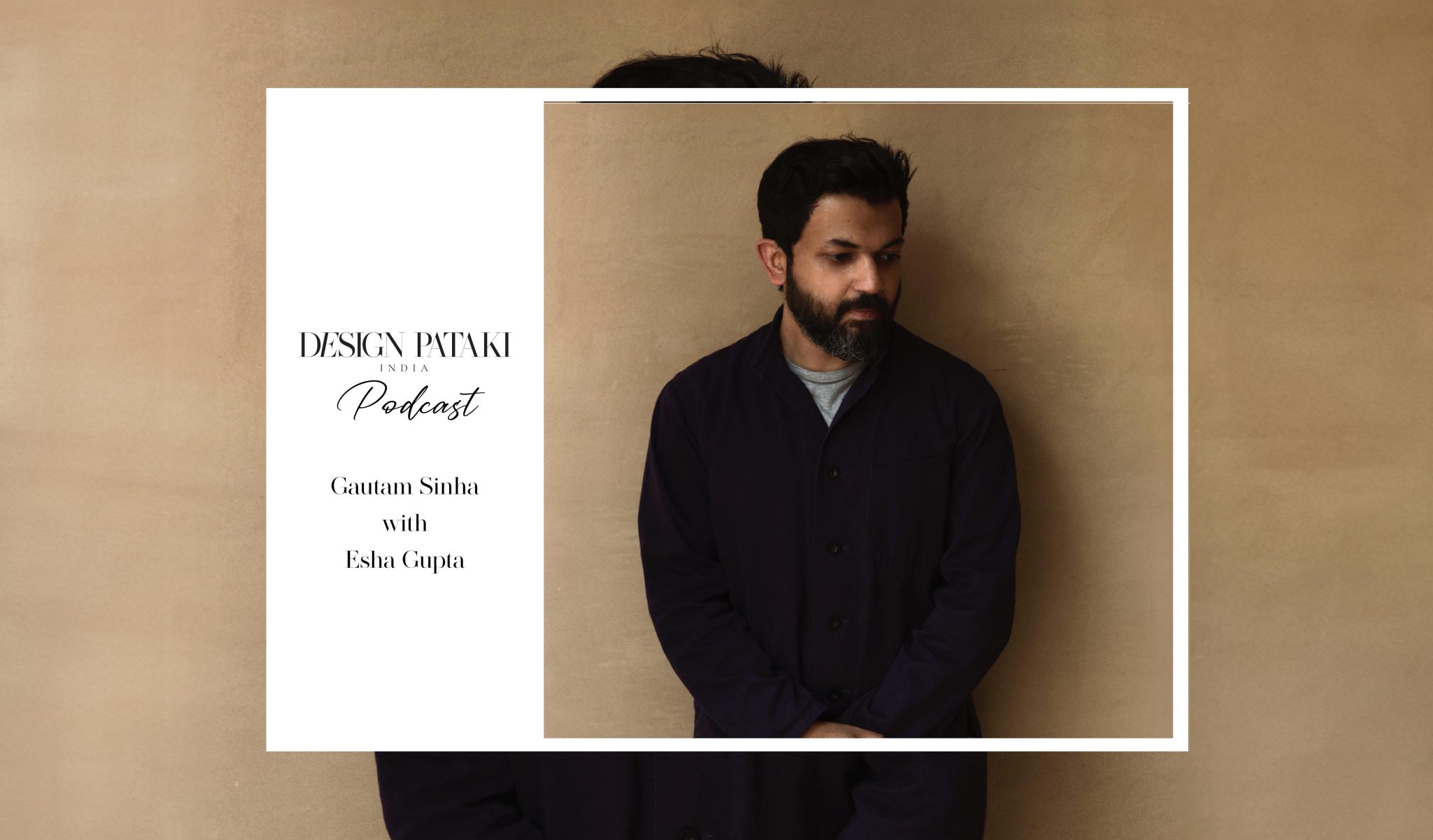

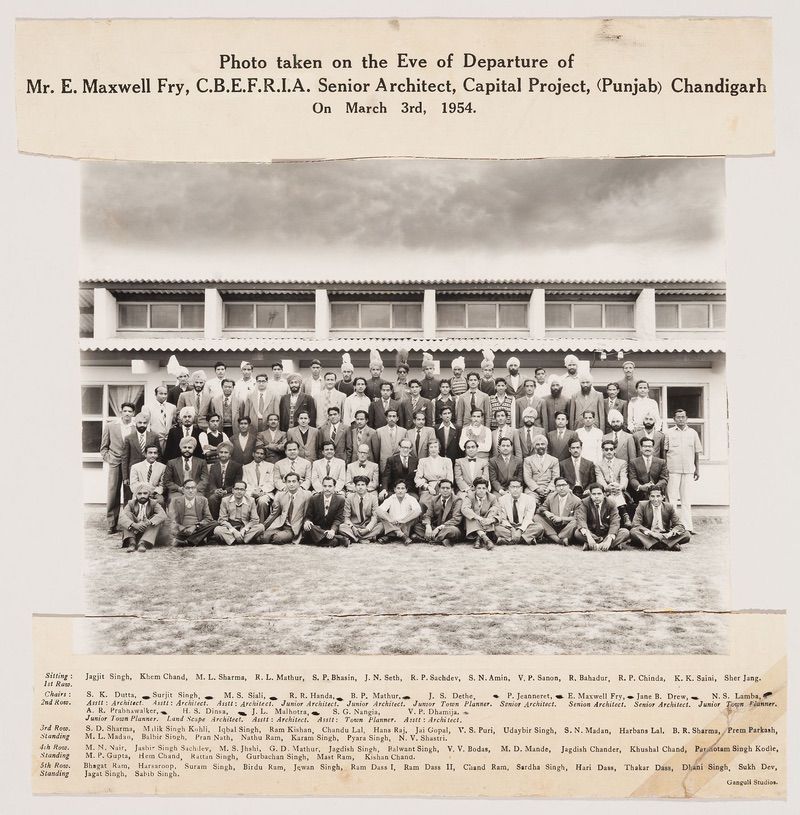

Shortly after Independence, as we all know, our first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru envisaged Chandigarh as the face of modern and independent India. Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret were engaged to design the Capital of Punjab in its entirety – roads, streets, sectors, parks, residential apartments for government employees, administrative buildings and their interiors. What emerged was a well-planned city dotted with iconic structures.

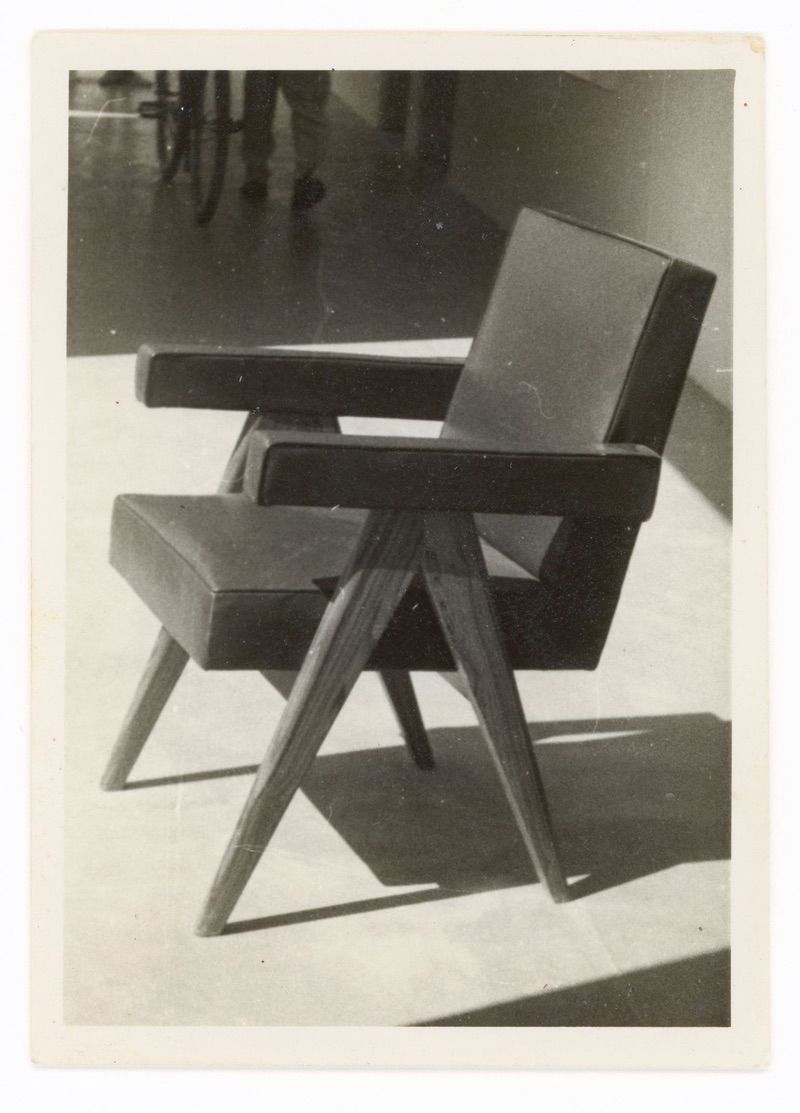

Even as debates about the relevance of Chandigarh’s design go on, its modernist furniture has caught the fancy of the rich and elite in Europe and America for several years now. The well-known American personality Kourtney Kardashian, reportedly, owns 12 Chandigarh Chairs. Chandigarh modernist furniture can be described as geometric in form with elegance, simplicity and functionality as its hallmarks. It was fuss free and made from teak and cane. The Bridged armchairs, X-shaped legs and particularly the V-shaped legs have earned themselves the reputation of iconic designs.

The furniture keeps surfacing in auctions held by Rago Arts, Christie’s and others where they command exorbitant prices. According to various newspaper reports, Bonhams auction house sold 10 pieces of Chandigarh furniture in October 2020 for INR 2.11 crore. These objects included a writing table, public bench, set of eight easy armchairs, folding screen meant for Punjab and Haryana High Court, Secretariat and Panjab University.

In another auction conducted by the London-based auction house Phillips in 2019, a sofa set designed for the High Court of Chandigarh and Assembly was auctioned for INR 34.80 lakh, while a pair of armchair was sold for INR 69.60 lakh. An executive desk for administrative buildings of Chandigarh fetched INR 7.39 lakh. This might evoke a sense of pride in some of us but design historians Nia Thandapani, Petra Seitz and Gregor Wittrick look at it critically. For some time now, the trio have been preoccupied with researching the history of Chandigarh Modernist furniture and the narrative around it. Their comprehensive probe into the subject forms ‘Chandigarh Project’.

“We are suggesting that a narrative around these chairs has been constructed that has shifted from the understanding of this furniture from being Chandigarh chairs to being Jeanneret Chairs, from being functional pieces to luxury design commodities, from being Indian to European, from being objects that were manufactured to being objects of high design,” stated Thandapani during their presentation titled “Chandigarh Chairs: Missing histories”, held in September this year as part of BIC (Bangalore International Centre) Streams.

How exactly did the furniture reach the European markets is quite interesting. According to an article in New York Times in 2008, the Chandigarh administration and its employees became disinterested in the furniture. Replaced with more glossy stuff, the old furniture landed in government storerooms. 1990 onwards, a slew of antique dealers like Eric Touchaleaume of Galerie 54 from France and other countries started visiting Chandigarh and buying the furniture from the government auctions. By the time the government realised its folly, it was too late as a large chunk of the furniture had already reached foreign shores. To save the remaining ones, the government stopped auctioning the furniture.

The first ever auction dedicated to Chandigarh furniture was held by the Paris-based auction house Artcurial in 2006 where 42 pieces were sold off for anywhere between US$5000 and US$21000. To date the team has analysed 1500 auction lots that have generated a data set of 2000 individual pieces that sold at various auctions conducted by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Saffronart and Rago Arts. To keep track of the latest auctions featuring Chandigarh furniture, they use a custom built software providing them with real-time auction data. “This data can shed light on how the furniture was designed, constructed and repaired in addition to provide solid evidence on how the current dominant narrative of Chandigarh Chairs has been constructed,” explained Seitz during the presentation. The team also analysed the material produced by the dealers who took the furniture out of the country. “This led us to study the narrative that has been created around the furniture to legitimise and support its sale in the west.”

Had it not been for COVID-19, the team would have travelled to access archival material on the subject. Speaking of challenges faced while pursuing research Thandapani says, “Much of the archival material related to Chandigarh is now in archives outside of India, in France and Canada, and it remains unclear the full extent of the holdings related to Chandigarh in these archives and with private collectors or dealers. Till now, archival material that has been used in publications like dealers books, is largely uncredited, making it hard to track down where the materials originate from.” This research is aimed at throwing light on the design ownership of the Chandigarh modernist furniture which is attributed to Pierre Jeanneret. In fact, Chandigarh Chairs are quite often referred to as Jeanneret chairs.

Responding to the questions on email, the team says, “In terms of design ownership, we believe it’s complicated but incredibly important to grapple with the hierarchy which existed within the team of architects and designers who worked on the furniture for Chandigarh, whilst still acknowledging individual agency of the people who worked within the team. It is clear that Jeanneret held a position of power within the team, but this does not mean that sole ownership was his. How do we better hold both of these ideas together and talk about this within narratives of Chandigarh, so that ‘ownership’ is not oversimplified? This is a crucial question for us.”

During the talk, Seitz revealed that Chandigarh Urban Lab headed by well-known architect Vikramaditya Prakash had created an inventory of Chandigarh furniture way back in 2009 and realised that not all the pieces were designed by Jeanneret. He worked with a team of Indian architects like Urmila Eulie Choudhary, Jeet Malhotra and Aditya Prakash on the furniture. The auction records have hardly given due credit to any architect other than Jeanneret. The auction records have hardly given due credit to any architect other than Jeanneret. “These are the main architects where there is documentation of their furniture work. But I would stress the point here is that more research is needed to establish who all worked on the furniture, including their work and others,” remarks Nia.

The other glaring omission is that of craftsmen and the various workshops where the furniture was handcrafted. It was only after six months of research that the team found out about metal tags present on some pieces. These tags indicated the workshops in Delhi and Patiala they were made in.

In the story of Chandigarh furniture, foreign dealers appear to have rescued the furniture from abandonment and disuse but Thandapani, Seitz and Wittrick dismiss it. According to them this narrative was created by dealers themselves and popularised through their books and literature accompanying exhibitions and auctions house sales.

“This picture of abandonment and disuse is based on uncredited and undated image, and anecdotal stories – largely from the dealers themselves. We believe that this furniture has importance beyond its financial value, in the value it holds from its use., The fact that the same furniture was in constant use in Chandigarh’s administrative and university buildings for at least forty years, and that some of it is still in use today, has conveniently been omitted from the popular history of the furniture which focuses on pieces that were apparently abandoned and disused,” express the researchers.

All three of them – Thandapani, Seitz and Wittrick studied design history together in London but they researched and wrote about different areas of design. While Thandapani is based in Bangalore running design Studio Carrom, Seitz is in London pursuing PhD from Bartlett School of Architecture, Wittrick is Assistant curator, Furniture, Textiles and Fashion in Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Thandapani says, “As we initially learned more about the Chandigarh Chairs history it became clear that it was a project where our interests intersected. While Petra worked on office interiors and labor, Gregor had been working on 20th century furniture, product design and craft, and I had been writing about mid 20th century Indian material culture and decolonisation within design and museum spaces. In this respect, the project was born from an interest in how these converging interests and skills might be able to bring a new perspective to the narrative we were reading.”